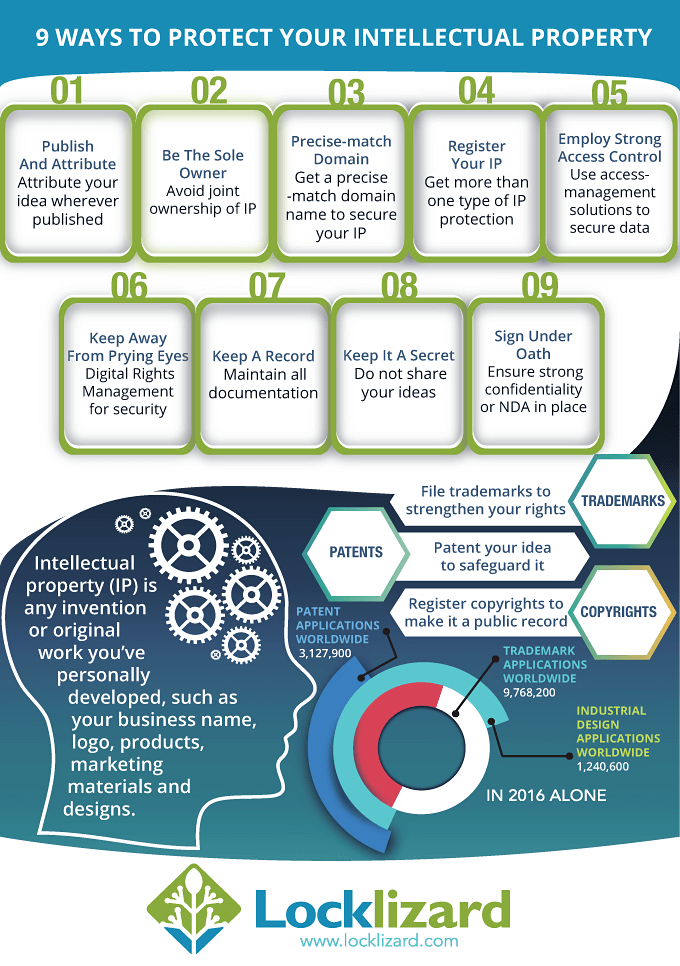

Digital Copyright Protection & Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

Intellectual property law is ineffective for copyright protection

Intellectual property law may establish the rights of authors and publishers, but it is not economically effective unless you are a substantial organization. This inherently disadvantages the entrepreneur and the small business who would look to copyright to protect their interests. Just as we have special regard to the rights of consumers we may need rights for smaller businesses, as we do in other areas of law such as in Unfair Contract Terms legislation. Special powers of controlling copyright works may be appropriate for small businesses that are inappropriate for larger ones who have effective access to law to protect their interests.

Free 15 Day Trial

Free 15 Day Trial

Protect documents – stop sharing

- Stop unauthorized access and sharing

- Control use – stop printing, copying, editing, etc.

- Lock use to devices, countries, locations

- Control expiry, revoke files at any time

Copyright and intellectual property rights (IPR)

Copyright and intellectual property rights (IPR) have been established and extended over many hundreds of years. Although initially developed to give a publisher control over the right to publish (copy) a work, they were extended to give rights to authors, painters, photographers, film producers and software writers (amongst many others).

Naturally, copyright protection was introduced as civil law because it was dealing with economic rights of one party against another. Criminal law was not appropriate, and, therefore, the state would not act on behalf of the copyright owner who had to take action themselves.

At the time that these laws were formed it might be argued that the only people who could create rights were those who were educated, and therefore rich.

Development of copyright protection

As education became commonplace for everyone (in many countries there is a legal obligation to ensure that children go to school) so the ability to create copyright works became something that (almost) anyone in the world could do.

At the same time there were debates about the wisdom of creating a system that would allow people absolute control over the copying and use of their works. Researchers and scientists could prevent anyone from checking or challenging their work. Political writers could ensure that what they wrote could only be seen by the faithful and never subject to proper criticism.

This may not seem to have much to do with stopping people from copying music tracks or DVD productions, but they were seen as significant problems that the legislators wanted to address. At the bottom of their thinking was the idea that nobody should be able to create a monopoly on knowledge. Just imagine if it was illegal to write about what was in a newspaper or quote a passage from a book or a film because copyright law prevented you from doing that.

Also, you could not have public libraries, schools and universities would not be able to provide books in support of some of their courses. Even teaching people about copyright works could itself be illegal.

Intellectual Property Law & counterbalance

But the problem is that to use copyright laws, for the small trader, the individual author or musician, is that you need to be able to afford litigation. This is because you have to wait for someone to break your copyright, and then sue them for the damage caused to you.

Let us take some practical examples.

You are selling something on a computer auction site and you create a very good photograph of it and some nice text that really helps sell it and make it attractive to the purchaser. You have maybe a dozen of these to sell.

The first sale goes brilliantly and you are already for the second when you notice that another seller has come in, is using your photograph and text, but selling the same item at half the price.

What do you do? You can try and get the auction site to take-down the other person’s advert, but they’re hardly that interested. You could try suing them, but the costs of starting a court action are in the thousands, and the most you’re likely to get back is hundreds because you have suffered little economic harm. But you’re mad as hell that someone can do that to you and there’s not a lot you can do about it.

Or you are a trainer specializing in management development and you have invested a lot of effort into a really good presentation and notes to go with your course. You give a few courses, and then find out that someone else is advertising the course and the material they are showing looks very similar if not identical to yours. But what are you going to do? Can you go on their course and take copies of their materials and then, if they are substantially similar to yours prosecute them? How much will it cost you, and how much can you get back?

Defending the small digital copyright owner

Probably the most difficult situation is where you have had to make your IPR publicly accessible. (The same goes for rock bands that perform live, DVDs that can be copied by pointing a camera at the screen whilst they are playing, and so on). There’s nothing much that you can do to defend against these situations no matter what you might want. The big film producers have trouble with this one, and if they can’t solve it you will be hard pressed.

Much easier is the situation where you do not have to make your work publicly accessible. This is the situation where you are selling a newsletter, magazine, training materials, course notes, books and so on.

Since the work is not publicly accessible you can impose controls over how it can be used and who can look at it (or print it or manipulate it and so on). This is much more powerful a situation, because you can limit who can see the work you can also limit their ability to copy it. (Do remember that you cannot stop people taking photographs of every single screen and then printing the photographs and scanning them to get back to text, but it is a big task to do something like that, so someone has to be really serious to want to steal your work and there must be good enough money in it that a legal action might work because the image is not going to be high quality.)

And that is where document DRM products such as Locklizard Safeguard are useful for digital copyright protection. They allow you to control all the way down to individual lengths of use or the ability to print. You can supplement and improve on the controls that PDF files have by integrating a licensing system over the top of existing controls.

Digital copyright & legality of controls

Now there are some potential problems with moving to what is effectively pay per view controls.

The law in most countries defines something called fair use, which means that people may see a work without charge for a number of purposes. A rights holder cannot refuse these rights any more than they can deny the right to free speech. So every small publisher faces the potential problem that they must allow anyone to have sufficient access to their work for legally permitted purposes.

This type of right was created to prevent monopoly of information, which the press barons or the film industry might otherwise create. (We also don’t want to get into a debate about the reasonableness of the film industry having a copyright of 100 years on the materials they produce.) But perhaps it is not appropriate when considering the small enterprise that requires specific protection?

Today we might need to think about a tiered system of digital copyright protection, where stronger controls are allowed in exchange for the fact that the copyright owner is not able to use the available law as an effective deterrent to copyright theft. The Internet has, on the one hand, made it far more possible for IPR creators to publish and sell their work, but on the other exposed them to far greater risk of having their IPR stolen as a result.

DRM companies such as Locklizard have developed licensing control systems for digital copyright protection that prevent printing documents, inhibit the use of print screen, and prevent anyone who is not authorized from seeing document content. Whilst this might not meet the requirements of fair use, it is the only effective way of protecting the ownership of the information. Because if the recipient is able to copy an electronic document then the genie is well and truly out of the bottle and no amount of ‘encouraging’ people not to do that will have any effect.

A compromize might be achieved by using licensing to allow anyone a single read only of a work without charge, but it would face some serious weaknesses. In the case of analyst reports their real value is the first time they are read. The same goes for training materials. They lose their sale value as soon as they are used, so perhaps they should be considered in a different way from traditional publishing of books and magazines.

Certainly achieving a balance between the rights of the copyright owner and the provisions of public policy such as fair use need to be debated with the very much broader range of people publishing electronic documents, and not just the big players, the libraries and the lawyers.